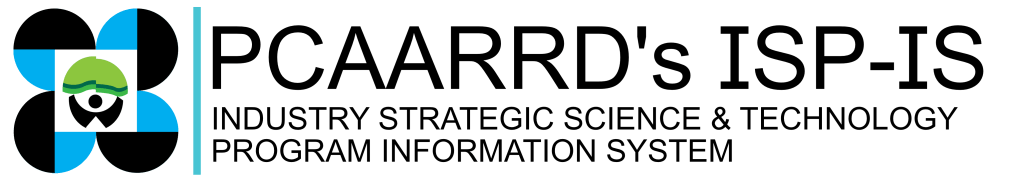

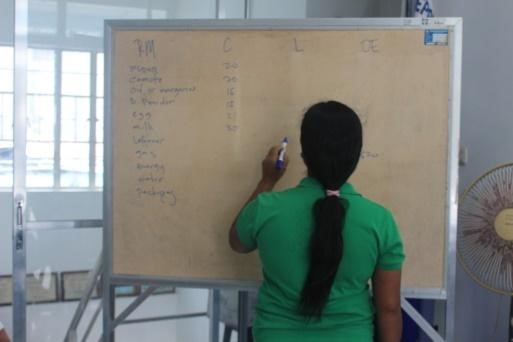

Sweetpotato Industry Profile

Sweetpotato, locally known as “camote” and scientifically named Ipomoea batatas L., is popularly known as the poor man’s crop in the Philippines. It is a nutritious food primarily consumed as a staple and vegetables. From a mere supplemental source of income to small farmers, sweetpotato has become a vital livelihood crop due to new and high market demand for sweetpotato products such as flour, confections, wine, and feedstuff. Based on the data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), as of 2019, Eastern Visayas remained the top sweetpotato producer with 98.95 thousand metric tons, sharing 18.8 percent of the total output in 2019. Bicol Region followed this with 16.0 percent share; Central Luzon, 9.9 percent; Western Visayas, 8.6 percent; and Caraga, 7.6 percent. The crop is commonly consumed boiled, fried, or roasted and is also used traditionally to create snacks and ingredients for various dishes. It can also be processed into different food products such as chips, noodles, and alcohol. Some products not for human consumption derived from the sweetpotato include animal feed and its use as a thickening agent.

Problems in the Industry

The following key constraints should be addressed to meet growing demands for the sweetpotato: 1. Lack of access to appropriate high-yielding varieties; 2. Inadequate supply of high-quality planting materials; 3. High pest and disease pressures; 4. Poor soil quality; and 5. Weak links to technology sources, markets, and commercial users. One challenge for the sweetpotato industry is the lack of suitable planting materials with high yield and high starch content. In addition, lack of information and technical proficiency in farming, compounded by the limited financial capability of farmers to purchase the necessary inputs, also limits crop yield and quality. Transportation costs for the fresh roots are also high, and there are a limited number of proper storage facilities. These factors jointly hinder further growth and production for smallholders.

Data Source: Philippine Statistics Authority update as of May 30, 2024.

Data Source: Philippine Statistics Authority update as of May 30, 2024.

Data Source: Philippine Statistics Authority update as of May 30, 2024.

Sweet Potato Policies

ISP for Sweet Potato

The ISP for sweetpotato aims to further boost the sweetpotato industry by developing continuous technological innovations mainly through value chain development and improved support systems concentrating on less-favored environments by the National Sweetpotato R&D.